Kung Future is a tiny NGO working in Phnom Penh off the smell of an oily rag, with landless Cham people who live on their boats at the conflux of the Mekong and Tonle Sap rivers. This week Kung Future reported the death of a two year old boy who fell off the boat he was living on and disappeared, despite the efforts of many who tried to find him by diving into the muddy waters. His body was found some days later. Kung Future do a lot of work in this community including organising birth certificates for children who would otherwise officially not exist; enrolling children whose parents cannot pay the fees, to school; some health care support when possible. They also provide upkeep for boats in disrepair, which often leaves families with no choice but to try and fill holes with whatever they can find, even rolled up paper! The community’s needs are high and the resources to meet their needs are extremely limited.

Meanwhile back in Australia, I feel a world away from all that. The Project is a current affairs entertainment show airing here on weekday evenings. One night recently, musing on a news item related to our national airline Qantas, one of the commentators said “every time I go on a plane…” as if it was the most ordinary statement, along the lines of “every time I eat breakfast…”. As ordinary as they may have seemed to most Australians, these words revealed the extreme privilege that simply being born in Australia bestows upon us. Our privilege is so normalised to us that we don’t see it. Not every Australian can speak so casually about plane travel, but every Australian can hear it with a feeling of mundanity. In contrast, I have lost count of how many seemingly worldly Cambodians have asked me with genuine fascination, about flying on an aeroplane, or how many countries I have visited.

Almost daily someone currently asks me if I find it difficult to settle back in at home. The biggest impression I have on my return is our normalised privilege. I don’t struggle with it at all; I am merely returning to my own normal life. However I do have a very heightened awareness of it after moving rapidly (in the space of a 10+ hour flight), from a place where survival and limiting hunger are the focus for a large proportion of the population, to a place where liberty and comfort are central to our reality. My friends and family here are securely employed, living in homes with solid roofs, paying off affordable and regulated mortgages, driving safely maintained cars, with opportunities to travel and the right to hold political opinions without fear. My friends in Cambodia have between none and a few of those things, on a much smaller scale and in a suffocating economy where poverty is a highly visible feature of everyday life.

Something else many people ask me is why I would choose to follow my plans to return to Cambodia rather than stay in Australia. A Cambodian friend suggested that maybe I don’t really love myself, that I would choose to live there rather than be among the comforts of my first world existence. Friends in Australia frequently suggest I need to focus on settling down / building a nest egg for the future. To the contrary, these quotes speak the most to me:

In The powerful way that normalisation shapes our world, Jessica Brown comments that “our grasp of normal is an entanglement of objective and subjective, moral and social judgements, prone to changing for the better and for the worse“. She highlights the complex nature of normalisation, in that it can easily change (eg the normalisation of various previously unacceptable behaviours during the era of Trump) but can also be very fixed (eg ideas on female beauty). It is an intricate phenomenon that most of us probably never really think about. The reason I think about it is because what seems normal when I am living in Cambodia, is very different to what seems normal when I am living in Australia and these differences are particularly heightened for me now, as I settle back into a six month stay in Australia.

As one of many examples, I am staying with friends at the moment, who due to some veterinary visits, have spent more on their pet dogs in the last two weeks than most Cambodians can spend on themselves in a year. These friends are living well, but they are not wealthy by Australian standards. Yet to my adjusting brain, sharing their lifestyle for this short time highlights how extremely privileged we in Australia are, with very little recognition of the fact because it is merely normal to us. It gives me some context to refer to, when trying to understand the complex nature of my relationship with impoverished villagers in Cambodia, who see me as infinitely wealthy. My existence is beyond their normality, for the sole reason that I have enough money to appear in, and disappear from their lives, seemingly at whim. Most of these are people who have never traveled away from their own village.

Before leaving Cambodia I wanted to visit Boat Baby, who I “caught” when he was born on the small wooden boat over the Mekong Delta in August. About six weeks ago now, I spent a weekend in Kampong Cham, visiting various people with Dan (tuk tuk driver), to say farewell. Boat Baby lives in the village next to the blind family who I have often talked about, so we added him to our itinerary in that direction and picked up an extra bag of rice for his family. Five months old, he was swinging in a hammock inside the family’s elevated bamboo shack as we arrived. He appeared to be asleep and I tried to stop grandma from waking him, as she bent to pick him up. As she did so, I realised he was awake, but with semi-closed eyes. A short conversation with Dan ensued, who then turned to me and with a tone of surprise said “Helen he is blind”.

Yet another vision impaired person in the same village? Can this really be just coincidence? My thoughts keep reverting to the knowledge that this area was heavily sprayed with Agent Orange in the 1960s. We will never know because this is not a place where researchers will spend money or time investigating, and even the American veterans exposed to Agent Orange, still reporting high rates of disability in their offspring, have had limited recognition. There is almost nothing written about it, but according to this article from 2008:,

Kampong Cham, Cambodia | The proportion of babies born with disabilities in eastern Cambodia is more than 50 times higher than in other parts of the country, according to local doctors.

While the reason for the higher rate has not officially been confirmed, it is generally believed to result from the use of Agent Orange, a dioxin-containing defoliant, by U.S. forces during the Vietnam War.

I was predictably horrified at the news and wanted to help. His grandmother was forced into the jungle in this area during the Vietnam War and remembers living as a soldier alongside the country’s Prime Minister, who also comes from this region. When I asked via Dan, does she know if they sprayed Agent Orange in the area, I understood her swift answer immediately – a very normalised “yes”.

The family had returned days prior from Phnom Penh, where doctors had already advised them to go to the paediatric hospital in Siem Reap where surgery may help. Having just traveled to Phnom Penh, they did not have any money for this and would have to wait. I gave them US$200 for the purpose of having him seen immediately but they could not leave now due to harvest commitments. Last week they finally took him to the hospital, a day-long bus trip, and were given a planned appointment for the end of this month.

My communications with Dan following this trip to Siem Reap not only saddened me but also highlighted the complexities of relationships such as mine with this family. A return bus trip and 1 or 2 days’ stay in Siem Reap would have cost a tiny portion of the $200 I had given them. So I was confused by their request via Dan, for more money to attend the next appointment. Dan never says anything bad about anyone, yet his reply to me when I asked why they needed more money already, implied that they had spent the money on other things assuming my money was free flowing, and that “everything not good” (ie he is unhappy with them).

Obviously I won’t continue to support the family in these circumstances. Which means the baby will either not receive any treatment for his congenital blindness, or his family will have to go into debt for the purpose. Health care debt is a normality in Cambodia where all health care works on a user-pays system. Poor families may receive discounted or waivers if they can produce a “Poor ID” card, however these cards are notoriously provided by village leaders to their own family, leaving the poorest in communities with no evidence that they need support.

In my world, people do the wrong thing all the time but they don’t have to pay for it with their health, the health of their children, or as is so often the case in Cambodia and other poor places, their lives. I feel very disheartened by this little boy’s circumstances and his family’s inability to understand the risk they took by making assumptions about my perceived wealth and perhaps my perceived obligation to him. Finding a balance in this situation is going to take some time, patience and soul searching.

- From Pew Research Center http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank

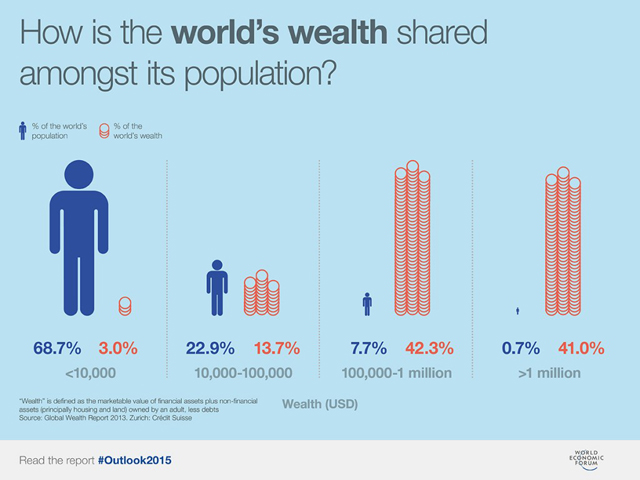

Anyone interested in where they fit into this scale of global wealth can enter their basic information into the calculator at GivingWhatWeCan.org. Despite my exposure to poverty which I think is probably more than most Australians, my hunch about my own wealth was completely wrong and I am far wealthier than I would have thought. That’ll be normalisation playing games in my head!

So sad to hear about Boat Baby, I have related the story of his birth many times.

LikeLike

Whatever’s good for your soul, do that.

LikeLike

More heartbreak. Who would have thought that the effects of that terrible war would be so far reaching & on-going. The huge waste that goes on in our world fills me with a feeling of despair sometimes.

LikeLike